My life before marriage and family raising

I (Alfred Simpson) was born at the General Hospital in Cobourg Ontario, on October 7, 1948. It was a cesarean section. My mother quit her job as a charwoman to take care of me until I was able to attend day school.

General Hospital Cobourg Ontario

My parents were Everett Vernon Simpson and Alberta Louise Whetung. I had an older brother, Edward Everett Simpson. My first memory was playing with a painted wooden train in my grandmother's house. It was 1953 and she had just finished her History of the Rice Lake Reserves. I was finally able to put her history onto the World Wide Web in 2001. I eventually became a web programmer because of my promise to publish her history.

My brother Ted was a much loved older presence in my life. He was so full of life and was a model for how to enjoy life. He hitchhiked all over the county until he received his driver's license. He held a variety of jobs throughout his working career. Everyone loved Ted. He found love late in life and lived passionately.

My mother read to me each night. Then, in July 1954 the family went to the Alderville Pow Wow, eight hundred meters away. In September of that year, I started attendance at the local Indian Day School. I was introduced to the alphabet and was amazed that anyone could remember all those letters. By the end of the next year, I had finished my first hardcover novel, Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi.

Ted and I at our first Pow Wow (1954)

Ted and I (1949)

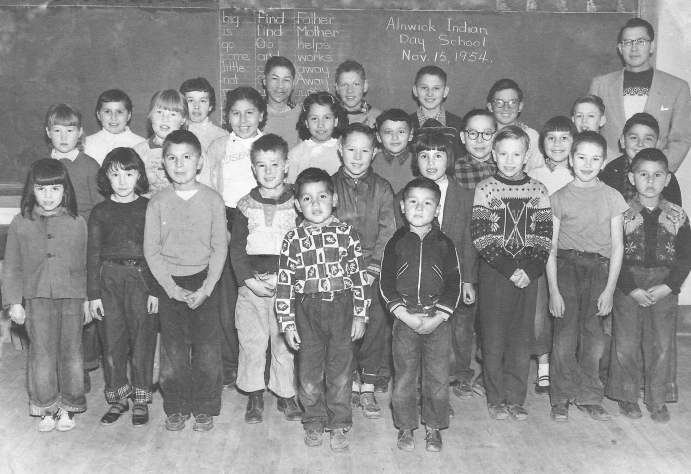

Alnwick Indian Day School 1954

When I started school, all eight primary grades were taught by band member John Loukes. The walk from my home was about 1200 metres so I was unable to go home for lunch. It was here that I learned how to interact with other kids. We played various outdoor games in the summer, baseball, and in the winter we brought our sleds to use on the adjacent slopes.

In November of that year, we posed for a class picture.

The curriculum included Canadian history taught from a purely British point of view.

We gladly sang.

In days of yore,

From Britain's shore

Wolfe, the dauntless hero came

And planted firm Britannia's flag

On Canada's fair domain.

Here may it wave,

Our boast, our pride

And joined in love together,

The Thistle, Shamrock, Rose entwined,

The Maple Leaf Forever.

Science and the basics of electricity were shown to the upper grades. Art seemed to be a large part of our studies. We each had ink wells in our desks and only used fountain pens.

A native point of view was never discussed. We followed the standard English Ontario Public School curriculum. I followed the adventures of Pierre‑Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers with great enthusiasm. My father was also a fur trapper so I empathized with those two French trappers. As "Father of New France" we studied the routes of the discovery of Samuel de Champlain. Peoples of North America's First Nations were rarely named and were deemed irrelevant to the aspirations of the European nations.

My family on a trip to Cleveland Ohio

Our community loved get‑togethers. We held celebrations throughout the year. Euchre card parties were ubiquitous. I remember being welcomed in homes throughout the reserve. Velma Marsden was my favourite host. This was a great way to know the members of our community. The main focal point was the new community hall which was built in 1954. Scheduled to be the first presenter, I was to say "Welcome welcome welcome" however, I was too shy to take the stage. There we held Valentine Day's celebrations, Hallowe'en costume parties, and Saturday social dances, where Chief Borden Crow played the saxophone. The dance floor was on the upper level with a stage, where routines were performed with fellow classmates. The dining area and kitchen were on the lower level, where my parents celebrated their 25th wedding anniversary.

The settlement of the Alderville reserve in Alnwick Township will be examined with the Methodist church assuming authority over the reserve until the Indian Act took control of First Nations lives. When the reserves were first formed, First Nations were encouraged to become either farmers or trades‑person, roles that were traditionally reserved for the 'lower class'. The Alderville industrial school was initially designed to train this 'lower class' and later was replaced by an Indian Day School on the same grounds as the old school. The Methodist church was there as well. Their intentions were good. Houses and barns were their first priorities to ensure a rural form of life, as opposed to a traditional First Nations lifestyle. Hunting, fishing and gathering were side issues and not valued as economic venues for serious income to sustain the community. Below is a link to specific information on the reserve where I grew up, (the first nineteen years).

The Indian agents strictly governed their charges with the supreme authority of English law formed by acts of law and the federal judicial system. The hunting, fishing and gathering activities were to be discouraged as this would keep their charges from the serious work of social dependence and servitude to the larger Canadian society. They were there to only provide food and other maintenance of trades‑person activities. These first inhabitants of Alderville were strongly encouraged to act like Europeans, but only in subservient roles. The First Nations peoples in the Bay of Quinte were removed from their homes to make way for settlers and their commercial enterprises. If ever an individual exceeded his role, he lost his official Indian status and had to leave the reserve. It could be argued that on‑reserve First Nations are still living under the strict conditions of The Indian Act of 1876.

A more personal view from the inside of the reserve system will be recalled showing a lack of cultural progress through the first century of reserve life. I was a subjective observer growing up on the Alderville First Nation in southern Ontario with no conception of the invisible boundaries surrounding reserve life. It was a very happy childhood and adolescence. My grandfather gave his time, imparting his very extensive knowledge of the details of farming. To him the grass that grows, even the trees were concrete examples of how to enrich our lives. My grandmother, although an integral part of reserve life, took it upon herself to research and document our personal history and migration to Alderville. My father showed me all aspects of our culture, including trapping, hunting, and rice gathering but was disappointed that I showed no talent as a carpenter. My mother ceaselessly raised a decent family. Her First Nations crafts, as well as her char duties, were done with pride.

Ted and I after my return from Camp Quin-Mo-Lac

There has been shown to be a lack of cultural progress through the first one hundred years of life on the reserve. I grew up on the Alderville First Nation in southern Ontario with a view that life outside the reserve was a foreign place. Traditional lore was passed down from my grandfather. He became what the early church was hoping the Indians of Alderville would become: i.e. farmers, hunters, and trades‑person. To water his crops, my grandfather learned the art of water witching. He taught me effective water witching. To find underground streams, he showed me a forked branch and said that a wooden dowsing fork must come from a tree bearing fruit with seeds. The well that they dug never ran out of water and was located dozens of metres away from my grandparent's house. He considered his front lawn a farm for dew worms. Well into his eighties, he got up in the pre‑dawn to pick dew worms selling each at the bargain price of a penny a worm to passing fishermen. My grandmother was involved in the early formation of the First Nations woman's Homemakers Association. This included the forming of quilting bees for use on the reserve. She taught Christian values at the local Sunday school, a duty which she took seriously. My Grandfather and Grandmother took on agricultural roles. They grew and raised potatoes, strawberries, raspberries, pigs, and chickens. They ate what they produced and sold the excess for profit.

I accompanied my father along his trapping line and he showed me how to set up the traps. He would return from a successful run in good spirits. The skinning was next, followed by the drying of the pelt on wireframes. We didn't forget the carcass which was baked and served for supper. Travelling north twice a year, he always brought back a deer, which was skinned in the basement and later he took the hide to the local tannery owned by The Breithaupt Leather Company in nearby Hastings Ontario, which closed in 1982. The carcass was cut up into strips and venison was stored in our large freezer. He was proud of his role as a carpenter because he could provide more than adequately for his family. My mother took on a job as a char‑woman in the local town, Cobourg Ontario. She also produced traditional First Nations crafts, particularly small birch bark containers decorated with porcupine quills, which added to the family income. My father and mother harvested black rice from local as well as distant rivers and streams. They regarded the gathering of black rice as farming. I went with my parents while they canoed through thick fields of beds of black rice. Dad paddled through the rice beds as Mom knocked the rice into the bottom of the canoe. Once home, Dad 'danced' the rice in a large iron kettle and used the wind to separate the rice from the chaff. This was a staple and well‑enjoyed treat. "The wild rice that grows abundantly in eastern Canada around the shores, of many lakes, makes excellent food, but only the Ojibwa collected it and used it to supplement their diet of berries, fish, and meat." (Jenness 1933: 16‑17)

The Alderville church left the Methodist fold in 1925 to join the newly formed United Church of Canada. The whole community was involved in church activities. A favourite was Mother's Day where a red flower was worn if your mother was alive and a white flower if she had passed on. Each family had its own wooden pew. It was very comforting to attend worship services as well as both weddings and funerals. It was a centre of community bonding.

My family was very close. My Dad, Mom, and brother Ted were my whole world. Dad was a hunter, trapper, gatherer, and carpenter. Mom was always there for me. We made long trips together, once to faraway Cleveland, where Dad worked in construction and played hockey with the local masons.

Ted, Mom and Dad in front of our home

1960 was a banner year for First Nations. On July 1st we became Canadian citizens which included the right to vote in provincial and federal elections. That fall six pupils from the Alderville Indian Day School were sent to the Central Public School in Cobourg for grade seven. The six of us were introduced to a more standardized curriculum that was now being given at Cobourg Public Schools. One of the new subjects was music. I scored 13% on my first test as this was my first experience in music basics. After much effort with appropriate materials, I pulled an 84% on my second test. This was brought to the attention of the supervising principal of all elementary Cobourg schools, Grant Sine. He seemed quite concerned about the discrepancy, so I mentioned my lack of music instruction at the reserve school. This was my only experience with that man.

Central Public School in Cobourg

I cried practically every day of that school year. I really did not understand the social dynamics of my new school. Mr. King was quite fair with all the students. Five of the First Nations students did not graduate in grade seven that year. I was the one exception and was promoted to grade eight.

My new teacher was Mr. Caldwell, the school principal. He liked telling personal stories and was quite lively in parting knowledge. As I was set to enter high school, he had a private meeting with my parents. He said that although my academic record was enough to get into high school, his personal view was that I would fail grade nine. When that happened, he told my parents that they should then put me into a trade school.

Amazing. On the first day of high school and we are introduced to a library.

We are given library cards and instructed in their use.

Ms. Rice was the librarian and the teacher associated with the library

facility was the grade nine English teacher Mr. Garcia.

He thought that I would make a good library assistant

and asked me to take that position. I declined and told him that I was

in no way capable of handling that responsibility.

He asked me to see him after classes.

There he laid out his theory of four kinds of people.

1) Those who know and know that they know should be followed.

2) Those who know and don't know that they know, they should be made aware

of who they are.

3) Those who don't know but think that they know, should be instructed to reality.

4) Those who don't know and know that they don't know, are content.

Alfred, he said, you are one of those who know and don't know that you know.

Five years later, at commencement, and after winning numerous awards, and

as I was lining up for my High School diploma, I saw him looking at me intently.

I then remembered those words from him on my first week in high school,

and in wonder, I smiled.

Cobourg District Collegiate Institute West

In grade nine, Mr. Sutherland was our science teacher and I began to learn how the world worked. Introduced to algebra, I was initially confused. I was only an average math student, but I eventually caught on to the mysteries of mathematics and got 100% on my algebra final at year‑end.

In grade ten, I was introduced to Physics, a wonder of wonders. The world around us could be described by mathematics! A banner year in mathematics class.

In grade eleven, another banner year in mathematics class. And I wrote the following essay on the IDLENESS OF MAN when in Grade 11A2, which received top grade marks. It was also printed in the Cobourg Star, the local newspaper.

"On the whole, man has for a long time been thinking about questions of his

surroundings. Why is there night and day? Why do things fall down and not up?

These questions have been answered by heroes of science all through time.

One of our greatest heroes of science was Sir Isaac Newton. He went on to think

about things, to study them, and to find out about the things around him.

Most people go on living a mediocre life, doing mediocre work, without really

trying to apply themselves. Newton asked questions about things that people

just took for granted. He not only found out how these things happened and

why they did.

In my personal experience, I have lived a mediocre life, like most people have;

having been shown that this was a mistake, I have tried to turn my life into

sharp awareness of things about me, which would enrich me, as it did Sir Isaac

Newton, The French writer, Voltaire, said, 'If all the geniuses of the universe

were assembled, Newton would lead the band.'

Alexander Pope, the leading English poet of Newton's day wrote:

'Nature and Nature's laws lay hid in night:

God said, 'Let Newton be', and all was light.'

There have been men, like Sir Isaac Newton, who have put everything into their

work, and have accomplished much; while others have put little into their work

and have accomplished nothing. This degrading fact of the laziness of people

trying to get through in life doing the minimum possible, without putting

everything they can into life or doing everything they can do, is disgraceful

and we should be ashamed of our past wastefulness. We should stop living a

mediocre life, and begin putting everything into our lives, so that we can be proud

of ourselves, instead of trying to be evasive of honest, hard work. If we cannot

stand up to ourselves and say, 'I do my best', we do not deserve what we have".

At the end of that year, I went to Camp-Quin-Mo-Lac on the southern shore of Moira Lake, a United Church-sponsored week of fun. We engaged in canoeing, swimming, and outdoor group games. My roommate Carl thought that I was a cross. I assumed that he thought I was half white/half black. He and I won the award for the cleanest room in the camp.

In grade twelve, I was introduced to chemistry. Mr. Dalgarno was a CDCI alumnus and he became very involved with the HS football club. That year I went with fellow geography students to Pennsylvania and upper New York State. I loved it. We went to natural caves half-filled with water. We toured the Corning Glass Works and saw the prototype of the six-foot mirror at the Palomar Observatory.

The Mackenzie Cup

In grade thirteen, with the help of Mr. Taylor and Mr. Dalgarno, I reached a peak in high school studies in mathematics, physics, and chemistry. I received a perfect score on the national Mathematics Scholastic Aptitude Test.

Mr. Brown who taught English gave me invaluable personal coaching so that the subject of English did not become a stumbling block. I was awarded the Mackenzie Cup for excellence in Mathematics. I finished high school with perfect attendance over five years. Needless to say, my parents gave me a nurturing environment so vital to success.

September 1967 started with a long drive to Waterloo with mom and dad and was the end of my residency in Alderville. I registered in the first freshman class in the Faculty of Mathematics. I took Calculus, Algebra, Computer Programming, Physics, Chemistry, and English. I did very well academically that year. I joined the Kairos youth group affiliated with the First United Church of Waterloo, where I also taught Sunday School.

The University Of Waterloo

I lived at 19 Elgin Street with Mr. and Mrs. Rempel who were Mennonites. My room-mate was Paul Martin, a student at Waterloo Lutheran University. His physics professor was once a student of Werner Heisenberg. My holiday return to Cobourg was my first ride ever on a train. On my return, I found that my room-mate had found accommodations on campus so that I had the whole upstairs to myself. The Rempels did not offer meals, and as Waterloo Lutheran University was halfway on my daily trek to uWaterloo, I ended up eating both breakfast and supper at the main cafeteria at WLU in my first semester. In the second semester, I took the full meal plan offered by St Paul's College within the uWaterloo umbrella. That food plan was so good that I put in my application for residence at St Paul's College going into my second year. My passion for Algebra and Computer Programming waxed exponentially in the second term.

Tenth letter to my parents on February 1st 1968.

Mr. & Mrs. Everett Simpson

R.R.#3, Cobourg, Ontario

Alfred Simpson

19 Elgin Street

Waterloo, Ontario

c/o David Rempel

Dear Mom and Dad,

I think it is a great idea that Ted and I will be able to go

to the West Coast this spring. It will come at just the right

time for me to relax from the tension of the exams. You have

definitely noticed that I am using my typewriter as I can put

more words down on paper at a faster rate. I have already

typed practically all of my English notes. Besides being more

legible the typing of my letters keeps me thinking when I

hear the steady hum of the keys.

Could you please send up a pair of scissors. I find that

the scissors will be practically invaluable to me. I have

just completed my third Math lab and I did not make any

mistakes so I should have not one bit of trouble in that

subject this term. Physics has become more interesting

this term as a new professor and my labs still average

over 75%. I wrote my major English exam of this term today

but I think I made out alright as the questions did not seem

too difficult. Getting away from my schoolwork, the Kairos

group at First United Church is really getting off the ground.

Although we only have about seven members we are a very

active group. The Session of our Church has voted our group

$100 to finance any project we feel will help our community.

We have also met with a few representatives of other Kairos

groups in the K.W. area; there our group was chosen to

organize a rendezvous of the some one hundred odd members

of Kairos in the Twin Cities. Due to the efforts of a member

of our group we have persuaded the national executive of

Kairos to meet here in Waterloo. Of course representatives of

our group will attend this meeting to prepare for the big

Conference this summer for about a week. It will be held in

Winnipeg August 26-30, at the University of Manitoba and the

delegates (there will be over three hundred representatives of

which I will be in that number if I can raise a maximum of $30,

there may be a National subsidy.) will have the use of all

the athletic facilities of the University. I have bought

cough drops to help with my cough so I should have no worries

in that department. I am glad to hear Pa is feeling alright.

Write soon and tell me about the arrangements of the trip.

I would prefer to go by train but I will leave that up to you.

Love,

Alfred

That summer I returned to Camp Quin-Mo-Lac before my second year started with my moving into St Paul's. My room-mate was Kim Zapf who had came down from Kapuskasing. He was another mathematics major, but he later switched to Social Work. He is now Michael Kim Zapf, Emeritus Ph.D.

Kim Zapf in Alderville

Kim accepted my invitation to spend Christmas back on the reserve. He was the skip of our mixed bonspiel team in nearby Hastings. I was introduced to Astronomy, another great love.

In September 1969, my third year I joined the volunteer Circle K club. One of our outings was at a dance held at the Ontario Training School for Girls - Galt. I was astonished that the majority of prisoners were First Nations. How did such inequities come to be? My room-mate was Dave Bagg a friend from the previous year. One of my close friends in the Circle K club, Essa Faraj a native African. He kept talking about his girlfriend Lynn, an anthropology student. They eventually broke up.

In September 1970, and again Dave Bagg was my room-mate. In my fourth year, I finally took Anthropology and studied my ancestral history. I became very close to one of my Anthropology class-mates, Lynn Catherine Gould. We didn't become romantically involved until February of 1971. At the end of the school year, we made plans for her to come to the reserve that summer. In late August I successfully applied for admission to teacher's college at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay.

May 1968, my brother Ted and I head off to beautiful British Columbia to visit our cousins in Saanich. We took the train both ways on The Continental. I loved the mountains. Our one movie on the Island was "Bonnie and Clyde".

Chateau Laurier Ottawa

In July, I showed up for work at Statistics Canada in Tunney's Pasture for programming support. In the lobby, a counter showed Canada's current population. I was very naive and everything was shiny and new. I lived at 57 Heney St, a boarding house costing $21 a week. Mrs. Ponzini and her sister provided wonderful meals plus a packed lunch. The only movie playing that summer at the Nelson theatre on Rideau St was "Gone with the Wind". I was asked if I wanted to attend a marijuana party with co-workers. I declined.

Chateau Frontenac Québec City

June 1969, my foray into learning French led to a summer job for the Indian Affairs Québec regional office in Québec City. I walked those narrow streets many times. It was a great experience. When I returned home I bought my parents an $850 colour TV, marked down by $100 for cash. My first-cousin-once-removed-ascending, Aunt Mary Simpson, remarked to my mother: "Lou, they'll never catch you now". The residents of the reserve were extremely competitive. I was very proud of my community for being so forward-looking.

June 1970, my first real experience living in Toronto. I worked at the Indian Affairs Ontario regional office next to the Davisville subway station. An adventure with another first-cousin-once-removed-ascending, Lucy Crowe, occurred when we shared a train car into Toronto from Cobourg. Aunt Lucy asked the railway ticket agent, 'when is the next train connection to Buffalo.' Upon learning that no train would leave until tomorrow, I used the payphone to call the Bus Terminal. I handed her the phone and she was able to determine that the next bus to Buffalo was in a couple of hours. Knowing where the Bus Terminal was located, I then helped with their luggage and we walked the few blocks north to the Bus Terminal.

Lynn and I at the family cottage

June 1971, Back in Ottawa. Lynn started the summer with a picked student initiative called Operation Beaver. The students built housing units in Chetwynd British Columbia. After returning to Ontario, Lynn came down to the reserve by bus. My parents picked her up in Marmora, and I came in later that day from Ottawa. We found the best restaurant in Hastings and took Lynn there. We even went canoeing on Rice Lake. As well, Lynn came down to Ottawa for a visit. I lived at 40 Cooper Street that summer.

September 1971, I took a flight to Thunder Bay and registered as an undergraduate in the secondary school teacher's program at Lakehead University. My room-mate was Jean-Guy Lauzon from Alexandria, Ontario. I started my first student teaching in Thunder Bay. That fall I asked Lynn to marry me(on the phone) and she said 'yes'.

Lakehead Campus

Over the Christmas holidays, I spent a day in Sarnia and met George and Gerry. They seemed quite relieved to see me. I wore my best suit in order to give a good first impression.

Over the Easter holidays, Lynn came up for four days. My friends got to see my fiancé. I bought my first electronic calculator. It could add, subract, multiply and wonders, it could divide!